读书笔记 -- 研究,是门手艺,The Craft of Research

The Craft of Research, Fourth Edition

(Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing)

book

Preface: The Aims of This Edition 论文写作 Our Debts

I. Research, Researchers, and Readers

note

跟读者建立联系 永远要知道你的读者是谁,他们想要知道什么;

读者知道什么了,他们接下来想要知道什么。

整个论文的写作,就是跟你的读者的一个无声的交流。

跟正常的交流不一样的是说,他不是互动的,而说你要一开始就想好,整个交流应该是一个什么的过程,要想清楚读者是谁,他们需要什么。

所以你在写文章时,而写的能满足他们的需求,使得他们能信服你写的东西。

Thinking in Print: The Uses of Research, Public and Private

- 1 Thinking in Print: The Uses of Research, Public and Private

- 1.1 What Is Research?

- 1.2 Why Write It Up?

- 1.3 Why a Formal Paper?

- 1.4 Writing Is Thinking

研究是什么: Gather information to answer a question that solves a problem.

写作的好处: We write to remember more accurately, understand better, and evaluate what we think more objectively. 写作使我们,记得更加精确,理解更好以及评估我们的想法是不是客观的。

- Write to Remenber 写文章自己会记得;

- Write to Understand 写的时候会帮助你理解事情;

- Write to Test Your Thinking 写作可以用来测试我们的想法;

论文格式,是同行交流的一个协议。

Write is Thinking Writing a research report is, finally, thinking with and for your readers. If instead you find a topic that you care about, ask a question that you want to answer.

需要为读者思考:去想自己的受众要去怎么样去理解这些东西,他们会怎么去想; 写作的核心在于,要找到一个 topic(自己真正关心的问题,并且自己真的想去回答的问题,就是说去找到自己的兴趣点在哪)。

Connecting with Your Reader: Creating a Role for Yourself and Your Readers

- 2 Connecting with Your Reader: Creating a Role for Yourself and Your Readers

- 2.1 Conversing with Your Readers

- 2.2 Understanding Your Role

- 2.3 Imagining Your Readers’ Role

- ★ Quick Tip: A Checklist for Understanding Your Readers

为你自己和读者都创建一个角色。 Research counts for little if few read it. Yet even experienced researchers sometimes forget to keep their readers in mind as they plan and draft their report. In this chapter we show you how to think about readers even before you begin your project.

读书或读论文时其实是跟作者的无声交流,写作也一样,是将自己的“声音” 写进文字里。 Writing is an imagined conversation. once we decide what role to play and what role to assign to readers, those roles are fixed.

作者的角色有三种:

- I’ve Found Some New and Interesting Information 发现了有意思的事,让大伙儿也乐乐(视频作者)

- I’ve Found a Solution to an Important Practical Problem 找到了实际问题的解决方案(有点像写博客)

- I’ve Found an Answer to an Important Question 找到了一个重要问题的答案,陈述问题与答案是什么(写论文)

当作者扮演不同的角色的时候,读者也会得到对应的角色。 读者的角色也有三种:

- 娱乐我。Entertain Me 追求娱乐的人。

- Help Me Solve My Practical Problem 需要解决实际问题的人。

- Help Me Understand Something Better 想要更好去理解东西的人。

没有找准读者的角色,可能会造成读者反馈: I don't care.

A Checklist for Understanding Your Readers

Think about your readers from the start, knowing that you’ll understand them better as you work through your project. Answer these questions early on, then revisit them when you start planning and again when you revise.

-

Who will read my report? 我们的读者是谁?谁会读我们的文章。

- Professionals who expect me to follow every academic convention and use a standard format?

- Well-informed general readers?

- General readers who know little about the topic?

-

What do they expect me to do? Should I 他们希望我来干什么事情。

- entertain them?

- provide new factual knowledge?

- help them understand something better?

- help them do something to solve a practical problem in the world?

-

How much can I expect them to know already? 理解一下你的读者的知识的储备。

- What do they know about my topic?

- Is the problem one that they already recognize?

- Is it one that they have but haven’t yet recognized?

- Is the problem not theirs, but only mine?

- Will they take the problem seriously, or must I convince them that it matters?

-

How will readers respond to the solution /answer in my main claim? 要预测读者对你的回答以及方法做的反馈。

- Will it contradict what they already believe? How?

- Will they make standard arguments against my solution?

- Will they want to see the steps that led me to the solution?

整个论文的写作,就是跟你的读者的一个无声的交流。 跟正常的交流不一样的是说,他不是互动的,而说你要一开始就想好,整个交流应该是一个什么的过程,要想清楚读者是谁,他们需要什么。 所以你在写文章时,而写的能满足他们的需求,使得他们能信服你写的东西。

1.2 WHY WRITE IT UP?

For some of you, though, the invitation to join this conversation may still seem easy to decline. If you accept it, you’ll have to find a good question, search for sound data, formulate and support a good answer, and then write it all up. Even if you turn out a first-rate report, it may be read not by an eager world but only by your teacher.

And, besides, you may think, my teacher knows all about my topic. What do I gain from writing up my research, other than proving I can do it?

One answer is that we write not just to share our work, but to improve it before we do.

1.2.1 Write to Remember

Experienced researchers first write just to remember what they’ve read. A few talented people can hold in mind masses of information, but most of us get lost when we think about what Smith found in light of Wong’s position, and compare both to the odd data in Brunelli, especially as they are supported by Boskowitz — but what was it that Smith said? When you don’t take notes on what you read, you’re likely to forget or, worse, misremember it.

1.2.2 Write to Understand

A second reason for writing is to see larger patterns in what you read. When you arrange and rearrange the results of your research in new ways, you discover new implications, connections, and complications. Even if you could hold it all in mind, you would need help to line up arguments that pull in different directions, plot out complicated relationships, sort out disagreements among experts. I want to use these claims from Wong, but her argument is undercut by Smith’s data. When I put them side by side, I see that Smith ignores this last part of Wong’s argument. Aha! If I introduce it with this part from Brunelli, I can focus on Wong more clearly. That’s why careful researchers never put off writing until they’ve gathered all the data they need: they write from the beginning of their project to help them assemble their information in new ways.

1.2.3 Write to Test Your Thinking

A third reason to write is to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, where you’ll see what you really can think. Just about all of us, students and professionals alike, believe our ideas are more compelling in the dark of our minds than they turn out to be in the cold light of print. You can’t know how good your ideas are until you separate them from the swift and muddy flow of thought and fix them in an organized form that you — and your readers — can study.

In short, we write to remember more accurately, understand better, and evaluate what we think more objectively. (And as you will discover, the more you write, the better you read.)

1.4 WRITING IS THINKING

Writing a research report is, finally, thinking with and for your readers. When you write for others, you disentangle your ideas from your memories and wishes, so that you — and others — can explore, expand, combine, and understand them more fully. Thinking for others is more careful, more sustained, more insightful — in short, more thoughtful — than just about any other kind of thinking.

You can, of course, take the easy way: do just enough to satisfy your teacher. This book will help you do that, but you’ll shortchange yourself if you do. If instead you find a topic that you care about, ask a question that you want to answer, then pursue that answer as best you can, your project can have the fascination of a mystery whose solution richly rewards your efforts. Nothing contributes more to successful research than your commitment to it, and nothing teaches you more about how to think than a successful (or even unsuccessful) report of its product.

We wish we could tell you how to balance your belief in the worth of your project with the need to accommodate the demands of teachers and colleagues, but we cannot. If you believe in what you’re doing and cannot find anyone else who shares your beliefs, all you can do is put your head down and press on. With our admiration.

Some of the world’s most important research has been done by those who persevered in the face of indifference or even hostility, because they never lost faith in their vision. The geneticist Barbara McClintock struggled for years unappreciated because her research community considered her work uninteresting. But she believed in it and pressed on. When her colleagues finally realized that she had already answered questions that they were just starting to ask, she won science’s highest honor, the Nobel Prize.

II. Asking Questions, Finding Answers

note

关于是 怎么样去问问题,怎么样去找答案。

- From Topics to Questions

- From Questions to a Problem

- From Problems to Sources

- Engaging Sources

你先找到大小合适的话题,然后问一些问题,然后把一个读者认为值得去了解答案的问题抽出来,做成一个研究问题。

研究问题可能是实际的也可能是概念上的,那不管是哪类问题,你都要想清楚,一它的状况是什么,二不解决它的话,它的后果是什么,但后面两节是说给一个问题的时候,你怎么样找到。资源就是找到前面的工作,然后怎么样读懂别人的工作,以及把你的工作放在别人的工作之上。

就是话题、问题以及它的后果。

- ★ Quick Tip: Creating a Writing Group

- 3 From Topics to Questions

- 3.1 From an Interest to a Topic

- 3.4.1 Step 1: Name Your Topic 你的话题是什么?

- 3.4.2 Step 2: Add an Indirect Question 你在这个话题里面的问题是什么?

- 3.4.3 Step 3: Answer So What? by Motivating Your Question 为什么别人会在意这个事情。

- 3.2 From a Broad Topic to a Focused One

- 3.3 From a Focused Topic to Questions

- 3.4 The Most Significant Question: So What?

- ★ Quick Tip: Finding Topics

- 4 From Questions to a Problem

- 4.1 Understanding Research Problems4.2 Understanding the Common Structure of Problems

- 4.3 Finding a Good Research Problem

- 4.3.1 Ask for Help

- 4.3.2 Look for Problems as You Read

- 4.3.3 Look at Your Own Conclusion

- 4.4 Learning to Work with Problems

- ★ Quick Tip: Manage the Unavoidable Problem of Inexperience

- 5 From Problems to Sources

- 5.1 Three Kinds of Sources and Their Uses

- 5.2 Navigating the Twenty-First-Century Library

- 5.3 Locating Sources on the Internet

- 5.4 Evaluating Sources for Relevance and Reliability

- 5.5 Looking Beyond Predictable Sources

- 5.6 Using People to Further Your Research

- ★ Quick Tip: The Ethics of Using People as Sources of Data

- 6 Engaging Sources

- 6.1 Recording Complete Bibliographical Information

- 6.2 Engaging Sources Actively

- 6.3 Reading for a Problem

- 6.4 Reading for Arguments

- 6.5 Reading for Data and Support

- 6.6 Taking Notes

- 6.7 Annotating Your Sources

- ★ Quick Tip: Manage Moments of Normal Anxiety

A topic is an approach to a subject, one that asks a question whose answer solves a problem that your readers care about.

Even so, once you have a question that holds your interest, you must pose a tougher one about it: So what?

At that point, you have posed a problem that they recognize needs a solution.

III. Making an Argument

note

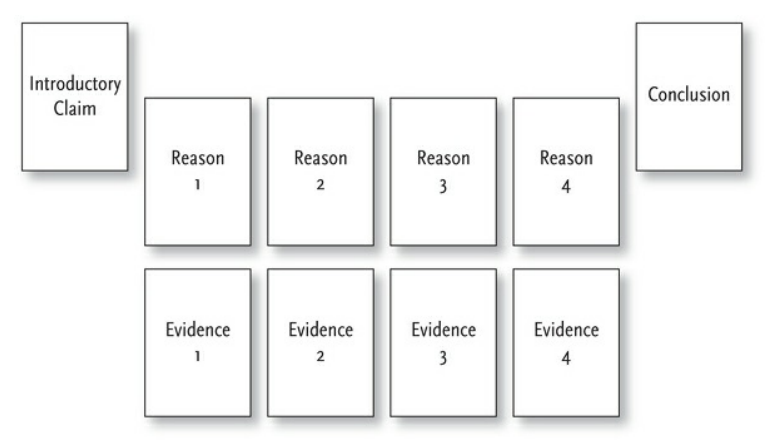

怎么样讲一个故事(怎么样提一个论点,怎么样安排论据来支撑你的论点)。

- Making Good Arguments: An Overview

- Making Claims

- Assembling Reasons and Evidence

- Acknowledgments and Responses

- Warrants

- III Making an Argument

- Prologue: Assembling a Research Argument

- 7 Making Good Arguments: An Overview

- 7.1 Argument as a Conversation with Readers

- 7.2 Supporting Your Claim

- 7.3 Acknowledging and Responding to Anticipated Questions and Objections

- 7.4 Connecting Claims and Reasons with Warrants

- 7.5 Building a Complex Argument Out of Simple Ones

- 7.6 Creating an Ethos by Thickening Your Argument

- ★ Quick Tip: A Common Mistake—Falling Back on What You Know

- 8 Making Claims

- 8.1 Determining the Kind of Claim You Should Make

- 8.2 Evaluating Your Claim

- 8.3 Qualifying Claims to Enhance Your Credibility

前情回顾:

- 写文章的时候呢要跟读者建立联系,因为我们写的文章最后是要给读者来读的;

- 在选题的时候要选择有价值的题,读者认为这个问题是值得解决的。

对大部分研究来讲,很难在一开始就能预测到我们想要怎么样的结果,如果在一开始就知道最后的方案是什么样子,结果是什么样子的话,很有可能这个就不叫研究,这个东西一般叫做工程。

- 工程就是我们一开始能想清楚答案,只要我们把它执行好就行了;

- 对研究来讲,我们通常要去探索未知的一些答案。

这个故事(research argument,学术的论点或论述)呢,就是用来回答所有我们可以预测的一些读者的问题。

如果整个这本书要抽出两个核心的问题的话,其实也就是 So What 和 我为什么要信 这两个问题。

7 论证的总览 Making Good Arguments

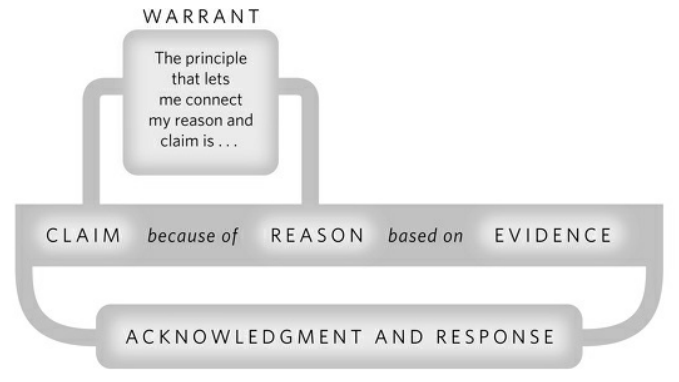

整个论证里面几个核心的东西:

- 首先要提出一个论点;

- 然后用一些原因和证据来支撑我们的论点;

- 有时候需要承认和回复一些别的观点;

- 最后有时候要提供一下你推理的一些逻辑的原则;

In a research argument, you make a claim, back it with reasons supported by evidence, acknowledge and respond to other views, and sometimes explain your principles of reasoning.

所以写作的核心是说,要在脑海中去预测这样子对话,使得在跟人真的对话之前,把所有这种可能性 —— 别人攻击你的地方,以及缺失的理由、论点、论据全部补充起来,这样子就能写出别人相信的故事了。

几个重要的元素:

- 论点:我们核心的理由是什么东西,很多时候文章最后就是一个核心的论点,当然论点还有别的子论点支撑; Claim: What do you want me to believe? What’s your point?

- 理由:为什么我们的论点是对的; Reasons: Why do you say that? Why should I agree?

- 论据:一些数据点或者别人的工作; Evidence: How do you know? Can you back it up?

- 承认和回复:对于别的一个观点的一个说明; Acknowledgment and Response: But what about … ?

- 保证:这个逻辑是怎么样过来的,如果读者不理解的话,应该把它说出来,解释一下我们的理由为什么能解释我们的结论好; Warrant: How does that follow? What’s your logic? Can you explain your reasoning?

理由必须是在论据之上的,结论是基于好的原因,理由又是基于好的论据;

- You have to base your claim on good reasons.

- You have to base your claim on good evidence.

7.6 要把 argument 弄得“厚一点”: 在支撑论点的时候,正正反反啊都要多讲一点,因为我们的目的是要通过这些比较厚实的论述,让读者能够相信我们所说的内容。

8 Making Claims 关于声明

怎么样去看现在想到的声明重不重要 :把结论反过来看一下反过来的那个结论是长什么样子。

But you don’t have to make big claims to make a useful contribution: small findings can open up new lines of thinking.

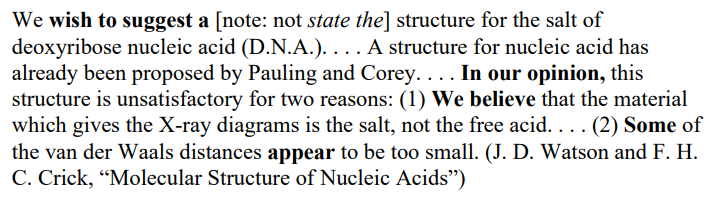

8.3 怎么样把论点变得更加可信一点 :

- 如果想让别人信我们说的话,最好不要把话说的特别的满;

- 可以承认一些局限性的条件。Acknowledge Limiting Conditions

- 要去想的限制条件的时候,是从读者角度来出发的。Use Hedges to Limit Certainty 从他们的角度来讲,去想想我们的理由也好我们的论据也好,在哪些地方更加薄弱一点, 把这些薄弱的地方作为限制条件给出来之话,那么对整个的可信度就会增加。

Of course, if you hedge too much, you will seem timid or uncertain. But in most fields, readers distrust flatfooted certainty expressed in words like all, no one, every, always, never, and so on . Some teachers say they object to all hedging, but what most of them really reject are hedges that qualify every trivial claim. And some fields do tend to use fewer hedges than others. It takes a deft touch. Hedge too much and you seem mealy-mouthed; hedge too little and you can seem overconfident. Unfortunately, the line between the two is thin. So watch how those in your field manage uncertainty and do likewise.

使用一些降低语气确信度的词,使得论点显得没那么的强硬:

- 如果讲的特别自信的话,读者会觉得更加的难以置信一些;

- 如果用了大量这样子的不确定的词汇呢,整个文章可能会显得比较弱,别人会觉得你可能自己也不是那么的确信。

- 尽量要避免这些词汇:all、no one、every、always、never 哈哈

- attention is all you need

- segment anything

- SOTA

一个好的论点一定是具体的而且是有价值的,可以通过把论点写的没那么满,使得读者认为你的论点解释出来更加容易一些。

要讲一个故事,让读者信你写的东西。 想一个故事和做研究是交错进行的过程,故事会随着研究的进展发生改变,因为很难一开始就预测到会得到什么样的研究结果。 也不能等所有实验都做完了写论文的时候再去想故事,这种情况往往要补做很多工作。 讲故事的时候,要不断站在读者的角度去思考,为什么要相信这个事情。 尽可能把所有读者可能攻击、疑问的点都考虑到,把相应的论点论据阐述清楚。 整个做研究的过程不断问自己 so what 和读者为什么要相信这两个问题基本就可以指导你的研究了。 此外,文中得到的结论必须要有相应的证据支撑。

9 Assembling Reasons and Evidence

- 9 Assembling Reasons and Evidence

- 9.1 Using Reasons to Plan Your Argument

- 9.2 Distinguishing Evidence from Reasons

- 9.3 Distinguishing Evidence from Reports of It

- 9.4 Evaluating Your Evidence

- 10 Acknowledgments and Responses

- 10.1 Questioning Your Argument as Your Readers Will

- 10.2 Imagining Alternatives to Your Argument

- 10.3 Deciding What to Acknowledge

- 10.4 Framing Your Responses as Subordinate Arguments

- 10.5 The Vocabulary of Acknowledgment and Response

- ★ Quick Tip: Three Predictable Disagreements

- 11 Warrants

- 11.1 Warrants in Everyday Reasoning

- 11.2 Warrants in Academic Arguments

- 11.3 Understanding the Logic of Warrants

- 11.4 Testing Warrants

- 11.5 Knowing When to State a Warrant

- 11.6 Using Warrants to Test Your Argument

- 11.7 Challenging Others’ Warrants

- ★ Quick Tip: Reasons, Evidence, and Warrants

我们有一个论点,然后通过理由,这个是能够架在我们的论据上面,理由是能够撑住你的论点的,如果中间任何一个部分没有做好的话,那么导致我们的论点是支撑不起来,就会导致大家不会信你。

So as you assemble your argument, you must offer readers a plausible set of reasons, in a clear, logical order, based on evidence they will accept. This chapter shows you how to do that.

在文章中间所用的证据只是对一个证据的描述,要确保两件事情:

- 证据的本身是能站得住脚的

- 对证据的描述是客观的

9.4 怎么样评估论据的好坏 EVALUATING YOUR EVIDENCE

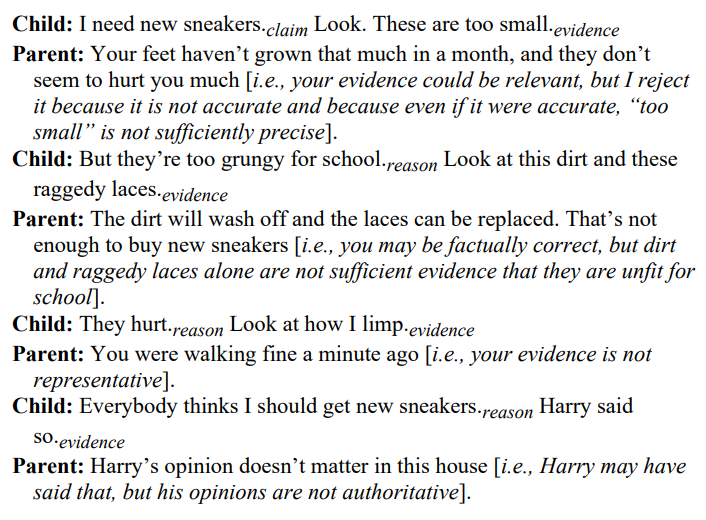

They want evidence to be accurate, precise, sufficient, representative, and authoritative. 一个好的证据必须是准确的、精确的、足够的、有代表性的和权威的;这里一个反例:

小孩哥的例子

9.4.2 要有合理的精度: 精确就说不要使用这种很模棱两可的词,而要使用一些比较精确的语言; 所谓的模棱两可的词就包括了 some most many almost often usually frequently generally 这都是一些比较模糊的词,我们要尽量得避免它。

10 Acknowledgments and Responses

But you can do it throughout your argument as well by anticipating, acknowledging, and responding to questions, objections, and alternatives that your readers are likely to raise along the way.

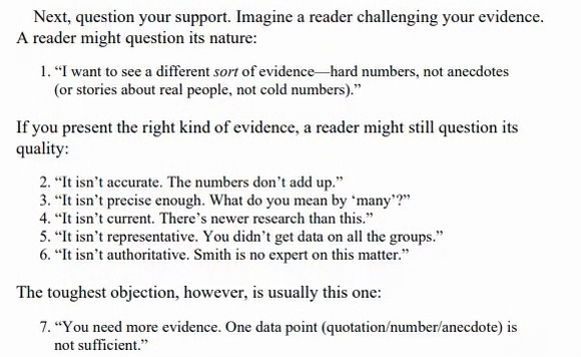

读者通常有两种方法去挑战我们说的东西:

- 内在的完备性,也就是说他们会挑战论点是不是讲的很清楚,然后理由是不是相关的,以及说论据的质量是怎么样的;

- 外部的完备性:包括了 是不是有一个别的方法来重新来讲我们的问题,或者是说 是不是有一些我们自己没有注意到论据,还有是说 是不是有别人的工作也写过相似的一些话题,但是他们提供了不一样的意见,我们并没有引用他们。

看一下自己这些原因和论据

11 Warrants 推理的保证

什么时候需要用到担保:

- 读者是在领域之外的时候(写教科书的时候经常会用它),大量的新来读者不清楚里面的一些隐藏逻辑, 把它给大家讲出来是非常有用的,不然读者可能会看不懂。如果说发一篇文章,必须要是自然杂志的话, 它的读者相对来说比较广的时候,也尽量要把这个领域相关的一些东西给大家写出来,让大家明白我们的这一个逻辑;

- 如果我们使用的原则对这个领域的读者来说,比较新或者是有争议的时候,也应该把它讲一讲;

- 当我们的论点特别有争议性可能读者觉得很难接受的时候, 那么在大家都会接受的情况下在前面说一些准则(如果他接受第一句,然后再过渡到第二句的时候)就显得没那么难接受一些。

我们选择去把这样子担保说出来时候,意味着是说我们其实关心读者,生怕他不懂我在说什么,所以把前面这一些逻辑给他们交代的更清楚。

关于怎么样去讲一个故事,故事也就是对你这个研究问题的一个回答; 我们的追求的终极目标是让读者信我们讲的故事,在这个故事里面有以下元素:

- 论点,也就是我们对研究问题的一个答案;

- 我们需要用很多原因来支撑我们的论点;

- 然后所有这些原因都应该架在读者能够信的这些论据上面的;

- 当原因和论点隔得比较远的时候,需要提供一些这样子的担保,来把整个逻辑说的更通一些;

- 不管我们提供多少原因去证明我们的论点,在读者读的时候总会有一些别的一些想法, 这时候我们如果能够提前预测出来读者的想法,然后承认他们并回复他们的话能够使得整个故事更加可信。

IV. Writing Your Argument

note

怎么样把这个故事给你写下来(关于写作主要在这个部分)。

- Planning and Drafting

- Organizing Your Argument

- Incorporating Sources

- Communicating Evidence Visually

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Revising Style: Telling Your Story Clearly

V. Some Last Considerations

- The Ethics of Research

- A Postscript for Teachers

- Appendix: Bibliographical Resources

- Index note

参考资料快照

- https://book.douban.com/subject/26883575/

- https://github.com/thongvhoang/CS519.M11/blob/master/The_Craft_of_Research_Fourth_Edition.pdf

- https://www.bilibili.com/opus/675153998359035925

- https://www.bilibili.com/opus/677787062451044354

- https://www.bilibili.com/opus/683058653961388073

- https://www.bilibili.com/opus/685577957002969110

- https://book.douban.com/review/15037339/

.

.